https://www.forgottenweapons.com/mounties-first-revolver-the-nwmp-adams-mkiii/The first handguns issued by the North West Mounted Police (which would later become the modern RCMP) were 330 Adams revolvers, requisitioned by the new police service in March 1874, and shipped over from England. Upon their receipt in July of that year, the Mounties were dismayed to find thoroughly worn out Adams Mk I 5-shot conversions from old percussion revolvers. These were found totally unfit for frontier service, and an appeal was sent back to England for something better.

A replacement shipment arrived in October 1875, and this time they received 326 much better Adams MkIII revolvers (330 were shipped, but 4 were stolen in transit). The MkIII pattern was a purpose-made .450 Adams cartridge revolver, holding six shots with a double action trigger and solid frame. These served very well, and the. NWMP ordered more in 1880 – for which they instead received Enfield revolvers, which had replaced the Adams in British military service by that time.

The 326 Adams MkIII revolvers issued by the NWMP were marked by a local gunsmith upon their arrival. The right side of the frames are marked “C M.P.” (presumably Canada Mounted Police) and given a police inventory number just below the barrel (in addition to the serial number above the trigger). These issue numbers were defaced when the guns were sold out of service.

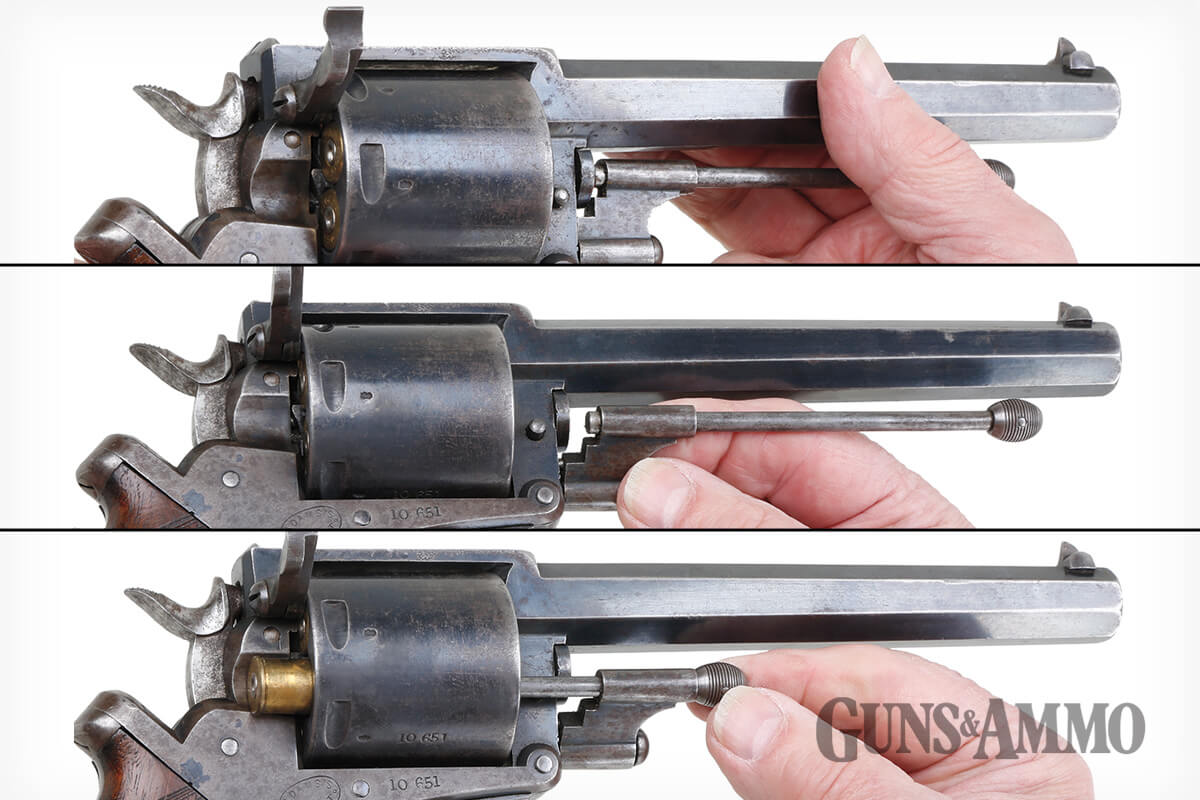

The Adams Model 1867A civilian modelrevolver featured a simple sliding rod ejector that was locked in place by a retaining lever. (Photo by Philip Schreier)

https://www.gunsandammo.com/editorial/the-adams-revolver-revolution/469340By Garry James

The year is 1870. Robert Adams is dead. Just four years earlier, the man who developed and passionately defended the first practical “self-cocking” revolver had closed his Pall Mall, London premises and moved to other quarters. Though he continued to sell the fine Beaumont-Adams revolvers that had been adopted by Her Majesty’s War Department in 1856, patent expirations and other matters had resulted in some financial difficulties.

His brother John, also in the gun trade, had introduced some interesting arms, most importantly some fine double-action percussions, coincidentally the same year Robert moved his operation. John had been enthusiastic about the possibility of converting percussion revolvers to fire self-contained cartridges.

John’s new revolver, designed in 1866 and finally patented in early 1867, featured an improved frame design and a slightly modified version of the Beaumont-Adams’ superb double-action lockwork, the main feature of the latter being the relocation of the sear to the rear of the triggerguard area. Though percussion, it would be found to provide an ideal platform for a breech-loader.

Centerfire revolver cartridges employing the important ideas of Col. Edward Boxer, superintendent of the Royal Laboratory and the Royal Arsenal at Woolrich, had first appeared in 1866, premiering with a stubby .577 round designed for a Webley revolver. A year later, a .442 load intended for use in Webley’s Royal Irish Constabulary line of repeaters and, in 1868, a .450/455 round built similarly to the .442 consisting of a formed brass case with attached, blackened iron base. The .450/455 was updated 9 years later with the iron base being changed to a hard-rolled brass one and the elimination of the earlier rounds’ cottonwool filling.

The precursor to the cartridge Adams, the percussion Beaumont-Adams (above, top), has similarities to its follow-ons. The Adams’ successor, the Enfield Mk I (above, bottom) was a totally divergent design and had a different chambering. (Photo by Philip Schreier)

Like Samuel Colt, Robert Adams was an enthusiastic, sometimes combative promoter of his wares. Early on he tried to interest the British military in his double action-only (DAO) Model 1851, head on its ejection rod. but the authorities thought it too complicated and parts not easily interchanged. They opted instead to purchase a number of Colt Model 1851 Navy revolvers for use in the Crimean War. The Colts performed their service well and were then returned to stores, some refurbished, and distributed to various entities, mostly in the colonies. Some officers did take privately purchased Adams self-cockers with them to the seat of war and reported back they found them perfectly acceptable, even in the harsh conditions of Crimea.

In the meantime, Adams had introduced a fine double-/singleaction (DA/SA) revolver that employed lockwork devised by Lt. F.B.E. Beaumont. This gun, which also featured the improved Kerr loading lever, was duly evaluated The Adams Model 1867A civilian model revolver featured a simple sliding rod ejector that was locked in place by a retaining lever. by the War Department. In January 1856, some 2,000 .54-bore (.442 caliber) pistols were ordered, the first of a larger quantity that would eventually find a home with the military. Though not available in time for the Crimean War, the Beaumont-Adams did see some action during the Indian Mutiny of 1857 where its performance was lauded.

This short-barrel commercial 1867, retailed by Boss & Co., shows kinship with its military colleague in that it has the military-style 1867B ejection rod. The rod could be pushed into an empty chamber as a safety device. (Photo by Philip Schreier)

The Beaumont-Adams continued in service, with a number of them eventually being converted to chamber the new .450 Boxer cartridge using a system devised by John Adams. The War Office designated the piece “Pistol, revolver, Deane & Adams, converted breech loader Mk I.” Even though good quantities of these five-shooters were altered in this way, today they are elusive on the collector market.

While all this was going on, John Adams, using his 1866 revolver’s frame design as a platform, came up with two wholly new six-shot .450 breech-loaders ultimately dubbed the Model 1867A and 1867B. Of excellent configuration, the same frame and inner works would also be used for the follow-up Model 1872. Let’s examine what differentiates one model from the other.

The rotating ejector rod on the Model 1872 was more sophisticated than that on the 1867 but was still awkward to use and could be a hindrance in a combat situation. (Photo by Philip Schreier)

The 1867s used a simple rod with bent-over, flattened head. It was mounted on the right side of the frame and had two stop notches, one to hold the rod in place when not in use and the other to allow the rod to be locked rearward into an empty chamber where it acted as a safety. This kept the cylinder in place when the pistol was on half cock, the hammer itself having no safety position, per se. The principal variances between the 1867A and 1867B involved the rod. The “A,” intended for commercial sale, had a small lever to hold the rod securely in its two positions. The “B,” which was also called the “Model 1867 Mark II,” had no such lever, the ejector being held in position by spring pressure on the detents. The pistol’s loading gates — also called “shields” by the manufacturer — hinged at their tops and rotated upward.

It appears the ’67’s ejection system was not deemed all that satisfactory, especially in the military version where the rod could easily be inadvertently pushed to the rear and jam up the cylinder. This was not a desired situation in the heat of battle. Accordingly, a new arrangement was initiated with the substitution of a slender pull-out ejector rod contained within a hole in the cylinder arbor. It was brought into action by simply extending it full length and then rotating it into position by means of a swiveling housing. While not exactly the fastest, it was more reliable in the field than its predecessor and accordingly adopted on August 24, 1872, as “Pistol, Adams’, Central Fire, B.L. (Mark III),” the War Office List of Changes succinctly explaining, “It differs from the previous pattern, Mark II … in having a more efficient extractor.”

Entering the service, primarily as a cavalry and officers’ arm, the Mark III was found to be an excellent, trustworthy piece of hardware. Complaints from the field were few, but there was some concern about the stopping powder of the .450 Adams round in which a 225-grain bullet at 650 feet per second (fps) produced a muzzle energy of 211 foot-pounds (ft.-lbs.). Compared to a contemporary Colt Single Action’s .45 Colt load, which fired a 255-grain bullet at 810 fps for a muzzle energy of 378 ft.-lbs., and the .44 Smith & Wesson Russian’s energy of 324 ft.-lbs. achieved by a 246-grain bullet with a muzzle velocity of 770 fps, the .450 was something of an also-ran. Granted, its ballistics surpassed that of the 1873 French Ordnance revolver’s muzzle energy of 195 ft.-lbs., but not by much.

Entering the service, primarily as a cavalry and officers’ arm, the Mark III was found to be an excellent, trustworthy piece of hardware. Complaints from the field were few, but there was some concern about the stopping powder of the .450 Adams round in which a 225-grain bullet at 650 feet per second (fps) produced a muzzle energy of 211 foot-pounds (ft.-lbs.). Compared to a contemporary Colt Single Action’s .45 Colt load, which fired a 255-grain bullet at 810 fps for a muzzle energy of 378 ft.-lbs., and the .44 Smith & Wesson Russian’s energy of 324 ft.-lbs. achieved by a 246-grain bullet with a muzzle velocity of 770 fps, the .450 was something of an also-ran. Granted, its ballistics surpassed that of the 1873 French Ordnance revolver’s muzzle energy of 195 ft.-lbs., but not by much.

The Colt, while also employing a solid frame and having to eject rounds one-at-a-time, had a superior ejection rod fixed on the right side of the barrel. The Smith & Wesson No. 3 Russian, American and Schofield revolvers, with their hinged frames and simultaneous ejection, were even more efficient.

Still, the Mark III was considered sufficient for use by Her Majesty’s forces and performed yeoman service in a number of arenas, most notably in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 and, for a period, with Canada’s Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) and units in Australia.

Loading the Model 1867 and 1872 was easily effected by putting the gun on half cock to free the cylinder and lifting the so-called “shield” (i.e., loading gate) to permit the insertion of a round. (Photo by Philip Schreier)

Studying other more powerful and efficient revolvers, the British War department set about a series of evaluations in 1880. They settled upon a top-break hinged-frame, double action employing an odd simultaneous ejector designed by American Owen Jones. When the revolver was opened, the cylinder slid forward and the gun’s stationary star extractor pulled spent cases free from their chambers. Though the pistol was apparently robust, it chambered a new .265-grain, .476 round, which really didn’t beat the .450’s muzzle energy by much. It was found that during extraction it was necessary to give the revolver a good shake to make sure a fugitive case had not gotten stuck in the action. The Enfield Revolver, produced in two models, was retired by the British after only 9 years of service, however, it remained in use elsewhere — especially with the NWMP into the 20th century.

The .450 Adams round (second from left) and previous and later cronies, respectively the .442 RIC, .476 Enfield and .455 Webley. (Photo by Philip Schreier)

The .450 Adams and two of its period military competitors. From the left: French Model 1873 11mm, .450 Adams, .45 Colt. (Photo by Philip Schreier)

Original .450 Adams cartridge (Left) and modern Fiocchi .450 load. (Photo by Philip Schreier)